Home

Publications

Publications

Showing 0 to 0 of 0 results

Statements

2025-07-02T09:21:44

ASEAN Foreign Ministers Must Act Now to Free Myanmar’s Political Prisoners, Say Southeast Asian MPs

Statements

2025-05-30T10:03:16

ASEAN’s Statement on Expanded Ceasefire Falls Short; Myanmar Crisis Needs Concrete Measures, Says APHR

Statements

2025-05-02T16:32:57

APHR FFM Reveals Alarming Crisis: ASEAN Must Demand Permanent Ceasefire and Protect Myanmar’s Refugees and Political Prisoners

Statements

2025-04-03T09:10:12

Southeast Asian Lawmakers Condemn Myanmar Military’s Obstruction of Earthquake Relief Efforts

Statements

2025-03-25T13:26:43

APHR Applauds Thai Parliament’s Initiative on Myanmar Crisis and Calls for Unified, Gender-Inclusive Peacebuilding

Statements

2025-03-04T11:11:00

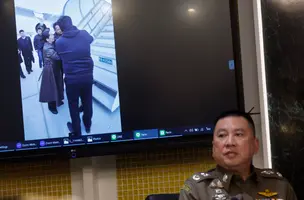

APHR Condemns Thailand’s Deportation of 40 Uyghurs to China, Warns of Grave Human Rights Violations

Statements

2023-11-17T17:15:19

Southeast Asian MPs call for international community to embrace localized approaches at Thai-Myanmar border to ensure humanitarian aid reaches the most vulnerable

Open Letters

2023-11-02T09:39:31

Open Letter to the Government of Thailand on Refugees Fleeing Myanmar

Statements

2023-06-28T13:15:44

Incoming Thai government must enact refugee-friendly policies, Southeast Asian MPs say

TOP

ASEAN Parliamentarians for Human Rights (APHR) was founded in June 2013 with the objective of promoting democracy and human rights across Southeast Asia. Our founding members include many of the region's most progressive Members of Parliament (MPs), with a proven track record of human rights advocacy work.

Copyright © 2024-2025 All Rights Reserved - ASEAN Parliamentarians for Human Rights (APHR)

Website by Bordermedia