ADVOCATE: Navigating Multiculturalism in Malaysia with Cynthia Lorraine Silva and Maria Chin Abdullah

October 10, 2024

INTRODUCTION

You’re now listening to “ADVOCATE” by APHR, ASEAN Parliamentarians for Human Rights.

Hello, I’m Lola Loveita, consultant for Freedom of Religion or Belief in APHR. I’ll be your host for today, and currently I’m with Cynthia Lorraine, a Community Media Program Officer from Centre for Independent Journalism, Malaysia.

Hi. You’re welcome. Thank you.

And Maria Chin Abdullah, former member of Parliament of Malaysia and APHR member.

Thank you for inviting me, APHR.

Today we will talk about the situation on harmony and multiculturalism in Malaysia and the role of Malaysian MPs and Southeast Asian MPs in promoting these values.

INTERVIEW

Joined APHR and Parliamentarian Works

Maria Chin Abdullah, you are currently a member of APHR. And before we dive deeper into the more specific issues, I’d love to hear a bit about your journey. How did you first get involved with APHR? Maybe you can share with us.

First, it’s because of knowing Charles Santiago and having been elected as a member of parliament for the first time first term. So I joined and I think I went for one of the meeting in Bali and I thought that it was a very useful network to be part of because it touches on issues that I am interested in. Like APHR has a section on democracy in the ASEAN countries. And also then I was invited to go to Oxford for FoRB kind of a training. And that was quite an interesting one. And so therefore my interest is there and I have continued even after I have left as a member of parliament.

What kind of work has been focused for you in Malaysia, YB Maria?

Mainly on the issue of democracy, elections. Elections is mainly because of my activist background. Being part of a coalition on free and fair elections. I have gone to one or two missions under APHR. The recent one was in the Philippines. I think that APHR is more active now on the environmental side because of the hype over the environment, social and governance indicators, ESG.

So the activities that are run by APHR are really down to earth related to what most members of parliament are talking about at the parliament level and at their country level. It is useful if more MPs and I hear that more MPs are interested, more MPs get involved in APHR so that there is a voice at the ASEAN level from the members of parliament talking about how we can actually build better democratic nations and how we can actually share information and support each other in times of crisis. That I feel is a very unique role of APHR.

And now that Malaysia is going to be the next chair for ASEAN, I hope that APHR will also play a big role in putting forward our agenda on democracy, on how elections can be run much more fairly, and also on this FoRB issue, it’s getting intensified, and it’s something that is a conversation that we need to actually be engaged in.

Maria Chin Abdullah, 2024

CIJ’s Work and Law Reform Advocacy

Cynthia, can you please share the primary areas of work that CIJ focuses on right now in related to Forbes issues?

Our primary work is on freedom of expression, where we prioritize media freedom, and also media diversity and plurality, where my job comes in. And also, we’ve been working on the right to information lately. Yeah. So I think that’s pretty much what we do.

Cynthia, if I can ask you, based on your experience and also CIJ experience, what do you think is the most effective entry point for the law reform advocacy in terms of promoting harmony and multiculturalism in Malaysia?

In terms of law reform, I think it’s very important to tackle first and foremost the laws that we already have, the archaic laws, I would say so we have plenty of legislations and plenty of instances where the law is weaponized to censor freedom of expression. It goes into everything that we do. It goes into what we want to say about the people who are determining the very quality of our lives, especially during elections.

So these censorship laws, I think we have this thing called SLAPP, Strategic Litigation Against Public Participation. And it’s basically weaponizing mostly legal means to silence or censor people, especially human rights defenders. So I think censorship laws really have to go. Things like the Communications and Multimedia Act, Sedition Act, you know, previously, back in 2020, we had this thing called the Anti Fake News Act. And that’s, that was also, it’s all used, as I would say, there’s a facade here where they use these laws that they say, oh, we need, like the CMA, right, or the printing publications, Printing Presses and Publications Act. These are all supposed to ensure, let’s say, safety or the quality of whatever we’re, let’s say, printing out or putting up on the Internet.

But it’s not, it’s all used to, basically, because there are provisions here that are so broad. The interpretation is so broad. So basically, amendments, in fact, there are many, many laws that I think the functions overlap. They’ve got to go. They don’t just need to be abandoned, they need to be abolished.

And, yeah, I think just looking at these laws, these censorship laws, and also, actually, on that note, we have what we call the, besides laws used to silence us, I think there’s also one, this law, the Official Secrets act, which we are looking into now. And I think it’s quite important to align, shall I say, the spirit of the OSA, the Official Secrets Act, with our incoming freedom of Information or right to Information act, because the OSA has long been used to basically tell people, stop asking questions, this is an official secret. That’s that. So that’s also another aspect to fetal expression.

I think that’s very, very important because harmony in multiculturalism, from a feudal expression aspect, it’s very important, I think, to basically allow discourse, but allow healthy discourse, especially considering the fact that there’s so much hate speech now, especially surrounding, you know, in Malaysia being a multicultural country, we have very, shall I say, sensitive topics or what people deem as sensitive topics.

But really there’s a huge lack of education as well on what it takes to actually have meaningful conversations around these things, around the reality that we live in, which is basically that there are going to be many, many cultures and many, many opinions. So how can we navigate that kind of discourse in a healthy manner in a way that doesn’t harm other people and it’s doable.

Obstacles in Legal Reform Advocacy

What do you think is the main obstacles in doing the advocacy for the legal reform, for those kinds of matters like FoE, FoRB, and harmony multiculturalism in Malaysia?

Honestly, it’s just the lack of a political will. I think it’s important to work together, obviously, with the executive, the legislation. Like, it’s very important for us to be able to get that kind of support. If you’re talking about reform or in advocacy for this kind of reform, if no one’s going to listen to you, then obviously it’s not going to go anywhere.

So I think, thankfully, I think so far the Freedom of Information Act is underway. And that took a lot of, I would say, I would say a lot of work, definitely a lot of advocacy and also the political will to have that, to be open to the idea of, oh, okay. You know, because the idea here is proactive disclosure. So it’s very important to have that kind of drive, you know, so the problem here is that, especially when you want to have laws and like you mentioned, right. It’s very complicated and also.

But I would say that there’s so, so many laws and there’s always this basis to kind of rely on three Rs. So in Malaysia, we have race, religion and royalty, which are the three topics that are, you know, they’re often used as few, you know, to kind of insight hatred.

But it’s also sometimes, I mean, there are instances where people bring up certain topics and they want to have, again, healthy discourse about it, but it’s, you know, it’s shut down. So that’s censorship. But you can also see that, especially in elections, you will see that these sentiments are then abused and they are used as chess pieces in a political game. So really it boils down to what does our government want? What do the MPs want, what does the opposition want? So it’s political will.

Legal Reform Advocacy of MPs

And Maria, from your experience, what’s been the most effective way to advocate for legal reforms that, especially for this issue, to promote harmony and multiculturalism in Malaysia?

First is whether the members of parliament and politicians want to engage in this, that we have to make more of them to be involved, especially when APHR, when it was actually having a collaboration with FoRB based in Oxford, that kind of training is very useful and it builds up a much more critical analysis of how we look at freedom of religion or belief.

And this is very real in Malaysia, as most of the time, politicians actually politicize race and religion in order to silence the other. So it’s a topic that we have to actually, first of all, have a change in attitude and be much more engaging in this issue.

Secondly, is really the nation, and even at the ASEAN level, we have to start talking about it. If we don’t, we won’t be building a narrative, a narrative that will actually reflect and strengthen harmony and multiculturalism, not just in Malaysia, but at the regional and international level. That kind of discussion is very important because in Malaysia, what does it mean by having a shared nation? And these are the issues, one of the issues that we have to discuss. If we are talking about a shared nation, then of course, we have to start reviewing the laws in Malaysia to see how we can actually strengthen them so as to discourage the hate speech, derogative kind of comments.

And this needs to be taken into account, not in a punitive way, not like how sometimes the present government tends to overreact to this kind of situation, but to actually also to prevent it getting too far, so that there has to be some review of the laws.

And also we have rather draconian laws, very undemocratic laws, like Sedition Act, parts of the Printing and Presses Act, which actually suppresses the freedom of expression. So people tend to be much, much more guarded when you have, you still have these laws and the government actually use these laws. And I would really like to have back that whole discussion of bringing back laws related to peace and harmony.

And also in 2018, the government then discussed about establishing an independent body to actually monitor the hate speech, provide education, engage in discussion, whether it’s interfaith or with other groupings. And that should be the direction that we want to go in order to build a much better shared nation.

So I truly, really want to encourage MPs to really provide that narrative. We have to start building that narrative. When we start reacting to other people’s hate speech or use of religion to politicize a particular situation, we become defensive. But I think that we have to take a different stance. We have to come out and say that, well, this is how we look at a shared nation.

And if you are part of this shared nation, you should actually respect differing views. You should actually respect that there are laws that actually discourages hate speech. And you should also respect that we can actually discuss in a much more amicable manner rather than shout and scream and bully people until they become silent.

Maria Chin Abdullah, 2024

I think we have so many examples of that, like the Allah being sewn onto the socks and it was only a few pieces. And there is this up and coming young politician making a big deal out of it and bullied everyone to silence. And that actually didn’t get that kind of responses from the general public, from NGOs and also even from the politicians.

There was like, I don’t know whether it’s a shock silence or that people weren’t ready to even engage or feel that this will blow over. It won’t blow over because these are the challenges that we have now. As the new government, under the unity government, tries to build what they call Madani Malaysia, then we have to actually start providing.

What is this Madani Malaysia that will bring to the table that will actually help us to build this nation, to be more respectful, build on harmony and build on trust and integrity.

Main Challenges as MP

Since you have touched about the law, I want to ask in terms of the legislative process, what were some of the main challenges you faced during your time as an MP when pushing for these reforms? Were there any particular barriers you consistently ran into at that time?

During my time, I think that the MCMC, the Malaysian Communication and Multimedia Act actually was the main stumbling block because it has section where this one is actually under the MCMC. It’s supposed to actually safeguard the interest and safety of users. But it has also been open to a lot, to some extent abuses where we see that it’s being used against activists. Some of the news portal have been blocked and that shouldn’t be the way to actually deal with the issue.

Anyone can actually disagree with the government, but there must be space created to actually consider some kind of discussion or engagement to talk about why this shouldn’t be done this way and how it can be done much better.

I think that there was a proposal from the ministry itself of the MCMC to actually even have license on social media sites like Facebook ads and TikTok, and also messaging services like WhatsApp. That shouldn’t be the way forward, because if we have freedom of expression in our constitution, there must be other ways of dealing with it. The usual way that most government tends to do is either they ban or they restrict, or they just completely block you into silence. And that doesn’t help to actually, for the people to actually build that inclusive narrative that we want to hear, that we want for this nation.

So even I think that there was even that proposal of a mechanism to hit a kill switch if the content becomes too aggregate. So that I feel that it kills a lot of enthusiasm to actually engage in any kind of discussion or expression. So I also want to see that when we were actually, meaning the Pakatan Harapan, to be precise, we did talk about getting rid of the colonial left behind Sedition Act, the Printing Presses and Publication Act, and also parts of the Communication and Multimedia Act.

We did say that we will either review them or actually revoke them. And particularly, I think that the Sedition Act needs to be taken off our law books, because this one is really open to not just abuse, but the way in which it has been crafted doesn’t really define what constitutes sedition. And so therefore, it really depends on whoever use it defines what sedition is all about. So that I think we can change, and I hope that this has been discussed also.

That’s why there was that discussion to actually relook at the Harmony Commission and also act to actually look into harmony and peace in Malaysia. So these were some of the ways that initially Pakatan Harappan government wanted to move forward with.

I hope that now we actually review that and have an independent commission that actually helps to set the standard to review and also to monitor and to also, if possible, to deal with some of these cases. So it’s really about the will to do it. And I think that we need to have strong will. It’s not just about appearing in podcasts or TikTok or any social media and talk about it, but the change has to happen at the parliament level.

Possible Mechanism or Intervention

I also want to touch on the report from CIJ that we used a lot during the mission, which is about the hate speech related with 3 Rs during the election, right, in Malaysia. I want to ask you about your perspectives on how this issue unfolded during the last election in 2022. And maybe you can also share the recent development of that kind of phenomenon, that the race of the hate speech at that time.

And also, is there any mechanism or interventions do you think were overlooked by government, by the MPs or by the CSOs, or by the independent bodies like MCMC or the EC that you think is overlooked on that matters?

So I think I can explain how we did the. What kind of things we noticed during the election. So we CIJ and our partners, we conducted a hate speech monitoring. So basically, we monitored social media. At the time, it was TikTok, X or Twitter, Facebook.

So what we did was we, of course, we identified based on certain topics. And we had also manual scraping of, so we used an automated tool, but we also had the help of human monitors to go and look through these platforms. And basically we called it manual scraping, where you kind of look through the data yourself and then you kind of do a bit more investigative monitoring.

So what we found was that, yeah, there’s certain sentiments. We narrowed it down to topics of race, the three Rs, race, religion, royalty. There was also gender, which is something that was played up quite a bit, especially during elections. And this. Well, I’ll get to the actors later, but. And then we also have the refugees and migrants, topics about refugees and migrants, which is also. There’s so much hate. And I think that one was the most. Shall I say, the chances of escalation were more. Yeah, it was more worrying.

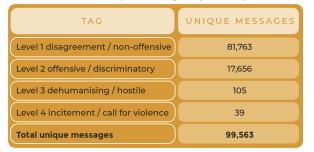

And actually, because when we looked through also on gender, we also had specific. We paid specific attention to the LGBTIQ groups when it came to how we classified hate speech. So we had levels. We had level one, two, three and four.

Basically, level one is just normal discourse. You have the right to disagree, that’s fine. I. But then you have level two, which is offensive remarks, you know, stereotypical things, you know, likening, oh, a certain race to, like, oh, these people always do this and that. And then they were also, I think especially during the elections, we saw that certain political parties were affiliated with the race. Like, there’s a racial aspect that was played up a lot.

And it’s not just. It’s not just by the people. You know, like, they will say, you know, let’s say people are ardent supporters or whatever political party, or they just wanted to. I don’t know why they would play it up like that on. I think we were thinking about what is it that really makes people tick? That makes people say the things that they say on social media, which they would obviously, otherwise, I don’t think you would hear anyone tell you this to your face, you know, or say this about anyone, but basically, you know, just likening people to animals, I think just saying, like, oh, you know, there was a lot of moral policing, especially in the gender aspect, because women, they’ll say things like, you know, things like that.

A lot of moral policing, especially of women politicians, which is, you know, I think it’s a online gender based violence, and that’s targeted towards demeaning the kind of work that women do. That was a remark, actually. So we monitored the general elections, the 15th general elections, two years ago.

Last year we also monitored state elections. And last year we saw that there was this MP who, he made a remark saying that, oh, you know, how women gonna, when you vote a woman in, you know, if there’s a flood in your area she’s going to take about 3 hours to get ready or something like that, and then she can, you know, then only she can help you. Things like that, you know. So I think that was also propagated through social media.

So I think, yeah, there’s definitely an element of amplification because of how accessible social media is. But I also think it’s because, again, you know, like people, I think when you sit behind your screen, there’s such a lack of education or awareness, really, of what your words actually mean. Or maybe they just don’t care or something.

There’s something about the anonymity that it gives you to kind of say things like this. And it’s, you know, I’m saying this like ordinary users, you know, I’m saying it as if ordinary users are the ones saying this. But really, no, we have political parties, key opinion leaders. We had, you know, especially for refugees and migrants. So I’m talking about level two, right?

So level three and four it escalates to is when the hate speech escalates to something more dangerous, where they say, oh, let’s kill this, and that group of migrants, of refugees, or basically all migrants, you know, let’s do this, let’s do that. And they will describe in detail how they want to kill these people sometimes. And it’s actually very, very worrying what people get away with in the comment section.

But also, again, like, it’s not just the users, it’s political parties, which is very alarming how freely they say this. And I think, yeah, I think there’s also, again, like I mentioned just now, right, it’s all pieces in a chess game. So I think there’s a lot of, like, a huge tendency to play up, you know, racial sentiments, religious sentiments, you know, or things like gender or especially the LGBTIQ community, because especially when there are spikes or, like, incidences.

Like, so last year there was this band, 1975, there was a bit of a stir because, you know, they had a, they shared a kiss on stage. It was the same sex thing. And. Yeah, so there was a lot of outrage. Regardless of what the opinion is, I think all the outrage online and all the harmful comments, you know, obviously that’s hate speech.

And also, like, politicians were jumping on the bandwagon. They were saying, oh, this is what happens, you know, and then they use religious sentiments. It’s often intertwined, all of this, you know, these sentiments, and they kind of weaponize that to garner votes or so. So basically, yeah.

And also something we noticed in GE15, the 15th General Elections, is there was this alarming hashtag that was coming up and it was saying, so Malaysia had riots, racial riots on the 13 May, we call it 13 of May, 13 May. On the 13 May incident, which is a very, very sensitive thing, I would say. But on, I think before and during the elections, if I remember correctly, on TikTok, you would see young people taking the social media profiles and going harsh.

This is what happens when this party wins or if this party wins, we go out and then they’re showing weapons. So that was very, very dangerous. We worked with TikTok at the time, and I think it was less, I mean, it was less alarming last year during the state elections for whatever reason. But I think also, yeah, I think that’s very important.

If you’re talking about mechanisms, interventions, I think it’s important to have conversations with social media platforms on what they’re actually doing.

Cynthia Lorraine Silva

You know, hopefully they care about what’s happening, I think, these days. Yeah, you’ll see that they do try because it’s a safety aspect and some would even say it’s a public security aspect for certain things. Yeah.

So in terms of how can parliamentarians address or mitigate this kind of thing? First of all, don’t use, don’t weaponize these things. Don’t weaponize race, religion. Don’t say, oh, they’re playing this game. So we will also play this game. The opposition is saying this whatever, for whatever reason. I mean, maintain the standards.

I think also our elections commission should be empowered. They should be mandated to look to campaigning ethics to kind of, you know, you should be able to have that kind of poll with political parties, especially during campaigning periods. Yeah.

And also, you know, we have to have some guidelines. We have to have guidelines on hate speech. What is hate speech? What is considered hate speech? Because, again, you know, there’s that thing about censorship. There’s always that worry. And even now, I would say our, you know, for instance, we have, right now, we have this, this thing called the Online Safety Bill, which is in works right now.

I think a concern, obviously, as it is with any other law, is, yes, you want to provide safety, and that’s very, very important. But where are the limits? You know, to what extent can it curtail freedom or expression? Because when people want to have a healthy discourse, and I’m not just saying this because, oh, this is a fear that it might happen. It already happens with our existing laws. Right. So, you know, if someone wants to talk about a certain thing, if someone wants to talk about how our government is actually dealing with certain issues or, you know, they should be allowed, you know, to say things.

I mean, I think previously there was an issue with, like, so I’m putting out a lot of examples, but I’ll try to cut it short. Yeah, but I think basically, yeah, there are issues where they say, oh, you know, oh, this pardon shouldn’t have been given to someone else. You know, someone just tweeted, I beg your pardon. And then they couldn’t, as a joke, you know. But then, you know, this thing is basically what people use.

It’s very, very easy, basically, to crack down on these people. So you really, really need to have clear guidelines on what hate speech is, you know, and how you should, topics that you shouldn’t touch. Moral policing. I mean, please don’t, don’t, don’t get there. You know, there’s no point. And it’s very gendered and it’s very archaic also. So during elections, just don’t touch those.

And also, I think the media plays a very important role because they do, there are certain outlets that do sensationalize kind of these issues, and then they play on the hateful narratives because that’s what’s popular, that’s what attracts attention.

Prioritized Issue

So what do you think from the perspective of CIJ or from you, what do you think should be prioritized right now for us to kind of prevent this issue from escalating?

I think continuous engagement with all. I mean, it’s a multi stakeholder approach. It has to be, you know, like, again, I think regionally we can support initiatives to kind of have these conversations, have these open conversations. And, I mean, obviously, I have to say there’s states of reference. So there is the issue of you cannot make anyone do anything, but you can set best practices. You can have these conversations. It’s very, very important to set the norm. Like you said, setting the norm is so, so important. And to kind of support each other.

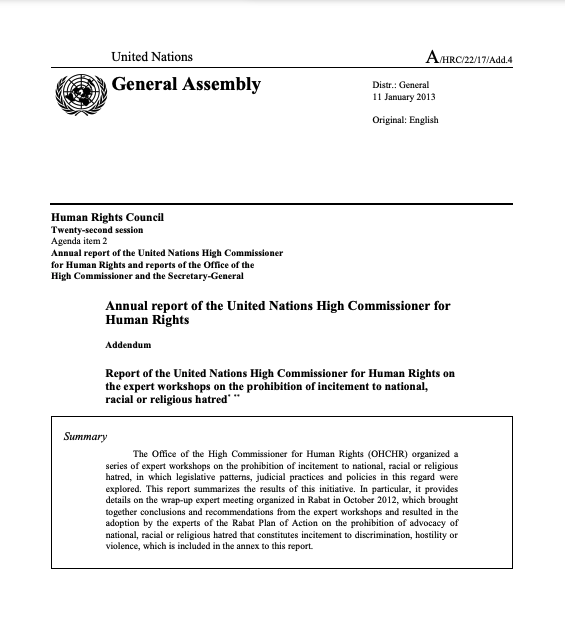

Regionally, I think we can support each other and to have regional initiatives that push for platform accountability, that push for conversations to parliamentarians, especially, elections commissions and so on and so forth, I think it’s very, very important to have a very united approach to this. I know that each country has a very different, you know, the context are different, yes. But regionally, I think we can all agree that this is a very prevalent issue, and there is a way to tackle this. And actually, I would suggest the Rabat Plan of Action when it comes to hate speech.

I think that’s a pretty balanced way of, you know, tackling hate speech and identifying hate speech without it censoring freedom of expression.

The Rise of Hate Speech

So, Maria, last year, I think in 2023 or end of 2022, we did this fact finding mission in Malaysia, and we tried to highlight the rise in polarization during elections, the time, especially on the role of social media in fueling hate speech. And it’s highly related with religion and race, etcetera, and some laws you mentioned, like sedition acts and section 233 of the CMA was, you know, being discussed a lot during our meeting with CSOs at the time.

And it was, it was true that one of the key findings, after we did some of the series of meetings with, with MCMC, with the Election Commission and a lot of CSOs there in Malaysia, that they said that it is true that there was the rise of hate speech at the time. And I want to know, from your perspective, according to you, like, based on your experience or based on your observation, how did that kind of things play out during the last election or, and post after the election?

I think the last election, we see a full blown use of TikTok as tool for campaigning, particularly by the opposition, Perikatan, PAS did it, as well as BERSATU and so forth. And I think that there is nothing wrong with using the social media, but it’s the messaging. And sometimes I feel that, you know, it is easier to actually politicize race and religion to pass a message on to the voters because these are the language, like it or not, agree or don’t agree. These are the kind of language they can understand about the other side. And it’s being used too much.

I think that it blurs the line between what is factual and what is misinformation. I would rather say it’s misinformation. So therefore, I feel that the role of the election commission has to come in and to be a bit more stronger in terms of when politicians or candidates use hate speech, derogative kind of words, and to run down another candidate, that has to stop or branding another person.

Personally, I have been branded so many things, including that I’m a liberal and that support LGBT without any proof, whether or any kind of evidence to show that any of these are true or not. And the whole issue of liberal has been so badly blackened that nobody. This reluctance to even be identified with liberal ideas.

But what is liberal ideas? Find out before you condemn that kind of ideas. Because ideas are just ideas. Ideas can be different from what you think. But why stop ideas? And why stop that kind of discussion? But in Malaysia, it tends to be to take the negative approach to either they put you down or say that your ideas are too out of context so that to tell the voters that, you know, don’t vote for this person because this person is going to bring down Malaysia or whatever.

And I think that, you know, the election Commission can set some standards over that. You can campaign, but we can still have a clean kind of campaign without having to run down another candidates. Because at the end of the day, I feel that voters need to hear what are your policies that you will bring to the constituents so that they can see their lives getting better, not just at the constituency level, but at the national level or even at the state level. If you are contesting the state assembly position, that should be the discussion that we should be having. Have open debates between candidates.

I remember in 2013, candidate one of the NGOs and even was organized by the church, San Francisco Xavier’s church, would actually bring all the candidates from all the different parties who are contesting to actually present their policies to the residents in Petaling Jaya. That is the way that we should be going. Present yourself in such a way that people understand that you are going to help us, you are going to work with us, and you are going to bring some changes.

That is what people want, not just build on them voting for you because you are, you know, one notch up on presenting hate speech or, you know, derogative languages and things like that. That’s not the kind of candidates we should be looking for or even voting.

It’s clear. Yeah, social media really amplifies a lot of these issues, especially during the last election. And TikTok. Yes, TikTok.

I think the problem with TikTok is that it goes so fast, there’s no time for you to verify how many, unless you are 24/7 in front of the TikTok to verify the facts or misinformation or disinformation that is coming out, you can’t verify. But that 30 seconds or that 1 minute TikTok remains in people’s mind and that actually brings them to the ballot box.

So I think that, you know, there has to be some way to actually empower voters. You can look at a TikTok, you can look at other media, social media platforms, but at the end, your decision shouldn’t be based on running another candidate down, but based on, hey, what is this candidate going to bring to my constituency? That should be the judge of how you vote for a candidate.

Potential Mechanisms and How can MPs Help

And based on that, Maria, what mechanism do you think were missed in handling this, for example, for the EC, for MCMC, or even the ministry and the government? And reflecting on your time during, as an MP in the parliament, what actions did you or other MPs take that could help in addressing this kind of issue?

Actually, when I, in 2018, there is this Ministry of Unity, and that was the ministry that actually started looking at possibility of setting, of reviewing the possibility of having a Harmony Act, and also setting up a commission. And I remember Mujahid Rawa actually talk about hate speech, possibility of a hate speech act, or at least the content of how we want to define and monitor hate speech to be included in the harmony act. So that kind of conversation kind of stopped when there was this change in government.

And that conversation needs to carry on. And it shouldn’t be just the Ministry of Unity taking up the issue, but it should be MCMC. In fact, the whole cabinet needs to talk about it, because this is the national question we have to answer, and that we have postponed answering it for a long time.

You see, the concept of Madani Malaysia, in a way, tries to bring about a much more inclusive, multicultural concept into Malaysia, to rethink that. But what the meat and the content hasn’t been fully worked out yet. And perhaps that is one of the big tasks that this cabinet, this government has to start doing to get the ministry talking about it, to get even the public talking about it, so that we are together at least for some common understanding of what we mean by multiculturalism, what we mean by having a nation where, you know, we can actually live with each other, be inclusive, and be respectful about differing views and religion and beliefs. So, hopefully, this government will actually start doing that, because it hasn’t got many years left before the next election.

How to Encourage Inclusive Dialogue

I want to go back to some laws you have mentioned, like Sedition Act, and some articles in CMA, of which the CSOs told us that it is harming the freedom of expression. And without freedom of expression expression, we definitely cannot talk about freedom of religion or belief. So, in your perspective, how can we encourage more inclusive dialogue on this issue, on multiculturalism and harmony in Malaysia, while also addressing these legislative concerns?

I think I would like to see inter ministerial initiative, you know, to start talking about it. And also at the parliament, we have all these select committees. They are, of course, tasked with different issues, but this is a cross cutting issue that all the select committees and even the ministries have to start talking about it.

So if it’s being initiated by the leaders from the top, I believe that, and translate it and work it out together with NGOs. At the ground level, we will be moving towards trying to resolve some of these tension, unnecessary tensions, to be honest, on hate speech, on disrespect for each other’s religion and belief. So I believe in conversation, in consultation, and we haven’t done that yet. We haven’t really done that. It tends to be done at a level of working in silos.

Only when crisis happens, then they start thinking about it, and the immediate reaction would be to ban or arrest or investigate. And that doesn’t help the situation, to be honest, the conversation is good because we are still at a level of searching for a better narrative. There’s no one narrative. There will be a variety, a diverse narratives. But let’s get down to talking about the narratives rather than hitting at each other through most of the opposition I’m using is, or even some of the unity government politicians are using hate speech or, you know, in defense of religion, to actually silence differing views. That is not the kind of narrative we should be moving towards.

The Role of CSOs

And in that matter, how do you think the relationship between the CSOs and, for example, interfaith groups and religious minorities groups, even parliamentarians, could be strengthened to promote this kind of collaboration?

I think that bringing them into the whole conversation is beginning. It’s not just minority groups, but Sabah, Sarawak. They have their own way of looking at the issue, and they seem to have a very different, different views, how they deal with race, religion and belief, and we can learn from them. And that conversation has to happen.

Why is it that they are reacting so differently from Peninsular Malaysia, where, you know, we are always up in arms when it comes to this kind of issues? So those kind of conversations has to happen. Whether you are the minority, marginalized, or you are the majority, all views needs to be heard. Otherwise we won’t be building any kind of narrative that is good for everyone, that we are able to be respectful to each other, not just tolerate each other’s existence.

Because tolerate can also mean that, you know, I still don’t kind of respect your views, but, you know, so we need to respect each other in the sense that, yes, we can have differing views, we can have differing views.

And I really would want the government to actually do what we actually set ourselves under, the reformacy movement, do what was actually intended.

That is getting rid of some of these acts that are open for abuse, particularly the Sedition act, and even some of these rather draconian acts like the SOSMA, because these are acts that can be open to abuse when the legislation does not give justice in a very fair manner.

The Role of APHR

What do you think should be prioritized by the MPs right now in terms of tackling repressive laws, especially related with the issue of multiculturalism and harmony in Malaysia? And how do you see APHR contributing to that matter, Maria?

I think the MPs should actually start looking into getting rid of the Sedition Act that is really a thorn in our law books, which actually doesn’t help very much to actually define what is seditious. How do you manage sedition and things like that? So that act shouldn’t be allowed to exist at all.

Maria Chin Abdullah, 2024

And also look at the MCMC, where you actually have quite wide powers to actually curb differing views. So these kind of laws need to be reviewed. And in the parliament, there is a select committee that is supposed to look at these laws.

And we have a minister, I mean, Azalina, who is in the law ministry, she understands these laws. And I would like to see that being taken up as their priority and to show the leadership that they should be, that they are supposed to show in bringing about the reforms. And these are not unachievable reforms. These are actually the low hanging fruits.

CLOSING

That was an episode of ADVOCATE by APHR, ASEAN Parliamentarians for Human Rights, supported by the International Panel of Parliamentarians for Freedom of Religion or Belief. Drop your ideas for podcast topics or interview subjects through [email protected] and let us know your thoughts on this episode. Before we sign off, I would like to thank you for your support and for tuning in. I’m Lola Loveita, see you soon.

ASEAN Parliamentarians for Human Rights (APHR) was founded in June 2013 with the objective of promoting democracy and human rights across Southeast Asia. Our founding members include many of the region's most progressive Members of Parliament (MPs), with a proven track record of human rights advocacy work.